Split is the second-largest city in Croatia (180.000 inhabitants) and one of the country’s most important ports. Its historic centre is definitely worth a visit, at least for a couple of hours.

We started our walk at the market. Although it was already late autumn – mid-November – the market was abuzz with all colors: apples, pomegranates, grapes, figs and other fruits. Other stalls were selling vegetables, including blitva (chard) – green leaves which are very popular in Croatian cuisine. In the adjacent small shops, there were shelves full of traditional meat products, jams, liqueurs, cheeses and other delicacies. The market by the eastern wall of Diocletian’s Palace is open every day, but Friday and Saturday tend to be the busiest.

After a few metres we came to the coastal promenade Riva. The big red letters SPLIT are definitely a favourite motif in the photos of many day trippers. However, probably not everybody notices the bushes growing nearby.

Even in November, one can still find a few yellow blossoms on them. It is aspalathus, and according to one theory, the name of the city comes from this word as the town was founded in the 3rd or 2nd century BC as a Greek colony called Aspalathos.

The sky was as blue as on a summer postcard. People were sitting on benches under palm trees. The only difference from the summer was that they were wearing coats and that the street was almost empty. Some people were enjoying a cup of coffee in the little cafes on the promenade. The backdrop to these cafes were the almost 2.000 year old walls of the former Diocletian’s Palace.

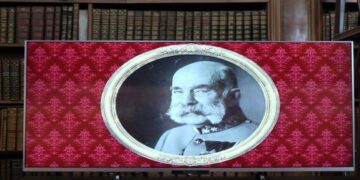

It was this monumental structure that was the destination of our walk. Because when we talk about the historic centre of Split, it’s actually this palace. Emperor Diocletian (circa 240-316) gathered the best architects and builders of his time to build him a residence here on this spot on the shores of the Adriatic Sea, 6 km from Salona, at that time the capital of the province of Dalmatia. During our walk, we saw several depictions of his palace, I have chosen this picture for you.

It is a pity that the names of the architects have not been preserved, so we do not know who designed this new type of building, which is a combination of a fortress and a sumptuous imperial residence. The ancient palace was rectangular in shape, the eastern and western walls were 215 metres long, the northern – 175, and the southern wall (which we viewed from the promenade) – 180 metres. The building occupied an area of 30.000 m², i.e. like one small city. As you can see in the picture, the palace originally had 16 towers; only three have survived. When Split was under Venetian rule, the towers were dismantled and their stone blocks were used to build palaces and churches in Venice.

The area is divided into two parts. The northern part of the palace was intended for manufactories and the accommodation of military personnel and servants, while the southern part contained the emperor’s living quarters and buildings used for religious purposes. Not only the shape of the building, but also the internal layout (two main vertical streets – cardo and decumanus) resembled a military camp.

There are four entrances to the palace, three from the land and one from the sea. There used to be no promenade like today, but this southern part was bathed by the sea. The smaller Brass Gate is located here. On the eastern wall is the Silver Gate, and on the western wall the Iron Gate. So let us enter the interior of one of the best preserved architectural masterpieces of late antiquity.

You have two options – either walk straight through this section and emerge on the upper floor, or buy a ticket and explore the ground floor as well – the substructures (podrumi) of the palace. I definitely recommend the latter option. On the one hand, you can cool off here on hot summer days, and on the other hand, you will get acquainted with the results of more than 50 years of archaeological research which has revealed a lot of interesting information about the structure of the building and its use not only in the time of Diocletian, but also in later times. Moreover, Game of Thrones lovers will be delighted to find themselves in the rooms where Daenerys Targaryen housed her dragons.

The perfect building elements will convince you of the admirable skills of the ancient builders. Their names have not survived, but you will still find masonry marks (letters of the Greek alphabet, religious symbols, etc.) engraved by them on the large stone blocks. These blocks fit together like tetromino shapes in the computer game Tetris.

The spaces of the former ground floor are truly fascinating. As the remains of the palace merge with the sprawling city on the upper floor, it is only here that you can best realise the gigantic dimensions and more clearly understand the layout of this imperial residence. The palace was built on sloping terrain. These substructures raised the southern part to the same level as the northern part, and created a structural support that allowed the construction of the imperial chambers on a higher floor, while protecting them from the sea moisture and groundwater. By the way, the palace was supplied with drinking water by a 9 km long aqueduct, much of which is still in use today.

We also saw the hall where Diocletian used to hold ceremonial banquets. There was also an ancient semicircular table made of precious marble from Asia Minor (now in the Split City Museum). In some of the rooms, the remains of columns, capitals and fragments of 16 different types of decorative stones are exhibited, originating not only from Asia Minor, but also from Egypt and Greece. The rarest is the red “imperial” porphyry from Egypt. Diocletian’s sarcophagus was also probably made of this stone.

We walked through those huge vaulted halls and rooms with the supporting pylons, admiring this masterpiece of engineering, and wondering: how is it possible that all this has been preserved in such perfect condition? It’s a paradox, but we owe it to the later generations of palace inhabitants and their careless attitude to rubbish… When the Avars and Slavs destroyed the nearby city of Salona around 650 AD, its inhabitants fled and took refuge within the walls of the former Diocletian’s Palace. Thus, a new city life began to develop on the upper floor, and everything unnecessary or used was thrown down to the ground floor. From the 7th to the 16th centuries, waste filled these spaces to the brim, and so they have survived almost intact to the present day. Archaeologists first penetrated through one window in 1956. Of the 28 interconnected halls, they have so far cleaned 25.

The former upper floor is an example of how the preserved remains of a Roman palace have been fused over the centuries with buildings of the Middle Ages and subsequent architectural styles. Today, there are cafes, galleries, shops, bakeries and, in one of the 15th-century Gothic palaces, the Split City Museum.

The Vestibule is the beginning of the corridor that led to the residential part of the palace. The circular hall with a diameter of 12 m has excellent acoustics, so don’t be surprised if you see a klapa-choir here performing a traditional Dalmatian form of singing.

From the vestibule, we reached the Peristyle Square, which is familiar to almost all visitors to Split. In summer, it is usually full of tourists, but now it was almost empty. From here, Emperor Diocletian addressed the inhabitants of the second part of his palace. Corinthian columns (some imported from Egypt), connected by arches, form the borders of the square. Diocletian also had 12 sphinxes brought from Egypt, the best preserved (from the reign of Pharaoh Tuthmosis III) one is in this square.

We also stopped at the temple dedicated to Jupiter, the main deity of the ancient Romans. Diocletian was considered his heir on earth. The Jupiter Temple was built at the end of the 3rd century, but later, in the early Middle Ages, it was converted into a baptistery, dedicated to St. John the Baptist. The building has a beautifully decorated portal and, in front of the entrance, you can see another sphinx made of black granite but without a head.

In Peristyle Square, you will also find the tourist information centre where you can buy tickets for the cathedral (5 €) and the bell tower (7 €). Diocletian was the first Roman emperor who decided to abdicate (in 305). He wanted to enjoy his retirement in his new residence in Dalmatia. Although he was again asked to return to the throne, he refused, preferring to stay in peace and work in his garden. Even today, his phrase “growing my cabbages” is used to illustrate the contrast between the grandeur of power and the simple pleasures of a quiet life. Why did he choose this place for his residence? He was probably born in the nearby area (Salona), the sea provided good defences and the local climate suited the emperor. He spent ten more years here.

Diocletian probably did not devote much time to his family, for his wife Prisca remained with their daughter in Nicomedia. Nevertheless, he was greatly affected by the news of their murder in 316, stopped eating, and is said to have died of hunger and grief the same year. He was buried in a mausoleum in his residence. The death of the emperor, however, was not the end of life in the palace. As I mentioned, new inhabitants moved in and adapted several of the buildings to their needs. They converted the Jupiter Temple into a baptistery and Diocletian’s mausoleum into a Cathedral (to the right of the bell tower), making it the oldest cathedral in the world still in use today!

Ironically, the final resting place of the merciless persecutor of Christians became a church dedicated to St. Domnius, the first bishop of Salona, who died a martyr’s death during the reign of Diocletian… It is a monumental building with an octagonal exterior and a circular plan.

Only a few elements remain of the original interior. Statues of pagan gods and emperors have been replaced by altars of saints and angels. It is not even known where Diocletian’s sarcophagus ended up. Note at least the relief strip under the ceiling with hunting scenes. Small figures with wings chase a wild boar (or a lion?).

The 13th-century hexagonal pulpit is made of rare green and red porphyry, and it is possible that it is the stone from the destroyed sarcophagus. The pulpit was built on six magnificent marble columns, each with a different capital.

And don’t forget to notice the beautiful walnut entrance door. There are 28 scenes from the life of Christ carved by local master Andrija Buvina in 1214.

The Bell Tower – a symbol of the city – was built later. The construction took extremely long time, from the 13th to the 16th century, which is why elements of both Romanesque and Gothic architectural styles can be seen here. However, I was fascinated by something else – how the tower fit into the ancient complex. It creates the impression that it has been there from the very beginning! The beautiful weather guaranteed a beautiful view. The tower is 60 metres high. I couldn’t resist and climbed the 180 steps to the top, but I have to say that the first part of the stairs is extremely uncomfortable and strenuous because the steps are very high.

The Bell Tower – a symbol of the city – was built later. The construction took extremely long time, from the 13th to the 16th century, which is why elements of both Romanesque and Gothic architectural styles can be seen here. However, I was fascinated by something else – how the tower fit into the ancient complex. It creates the impression that it has been there from the very beginning! The beautiful weather guaranteed a beautiful view. The tower is 60 metres high. I couldn’t resist and climbed the 180 steps to the top, but I have to say that the first part of the stairs is extremely uncomfortable and strenuous because the steps are very high.

The view was truly magnificent. I had the red roofs of the city below me, but also the walls of the ancient palace – the historical centre of Split, which was inscribed on the UNESCO list in 1979.

On the south side, I had a view of the sea, where the November sun was casting its golden reflections.

Then we walked around the rest of the palace area, each time surprised by a nice inner courtyard, garden, medieval palace or square.

If you walk here too, take note of the 14th century Ciprianis-Benedetti palace, where you can still make out the coats of arms of the two families, a relief of St Anthony the Hermit and a relief of Adam and Eve.

Slowly, we approached the endpoint of the Roman Cardo (now Diocletian Street). The gate in this (northern) wall is called the Golden Gate and was used exclusively by the emperor. It was through this gate that Diocletian stepped into his new residence on 1 June 305 (to grow his cabbages 🙂 ). You can still see that the gate was richly decorated. Even now, the sunlight has coloured the inside of the gate golden.

Outside the Golden Gate, you will find another famous monument of Split. It is an almost 8-meter-high bronze statue of Grgur (Gregory) of Nin by the internationally renowned Croatian sculptor Ivan Meštrović. It originally stood in Peristyl Square, but was dismantled during the war and then rebuilt on this spot. Bishop Gregory of Nin was the main proponent of the Old Slavonic language and Glagolitic script. I was already familiar with the not very friendly expression on his face, because Meštrović donated a similar, but slightly smaller statue to the town of Varaždin. In Split, as in Varaždin, the statue has a polished toe. Don’t forget to touch this toe too – perhaps it will grant you a wish or bring you luck.

After our long walk, a small snack at El Telegrafo Empanadas on Marina Držića Street, where we had managed to park the car earlier in the morning, was a good idea.

Text: © Copyright Ingrid, Travelpotpourri

Fotos: © Copyright Ingrid, Travelpotpourri

TRAVEL

TRAVEL

RECIPES WITH A STORY

RECIPES WITH A STORY

AUSTRIA-VIENNA

AUSTRIA-VIENNA

SLOVAKIA-BRATISLAVA

SLOVAKIA-BRATISLAVA

EVENTS

EVENTS

INTERVIEWS

INTERVIEWS

At the Festival of Waiters, Baristas, Bartenders and Restaurants in Split

At the Festival of Waiters, Baristas, Bartenders and Restaurants in Split